Lincolnshire’s Literary Worlds

A writer returns to her rural English home during the pandemic—and rediscovers the area’s rich literary landscape through works by Tennyson, D. H. Lawrence, Virginia Woolf, and more.

By Juliette Bretan

Over the last year—a year of lockdowns, constriction and confinement—space has become a precious commodity. Rooted since March 2020 in Lincolnshire, my oft-neglected, staunchly rural, and relentlessly flat home county, tacked on to the east coast of the UK, I’ve spent much of my time thinking about both physical and imaginary spaces—and reconsidering what makes the county such an interesting (if, at times, excruciating) place to live.

I’ve had a love-hate relationship with Lincolnshire for many years. The county, to some, is proper bucolic paradise: the Lincolnshire flag, in bright, bold blocks of blue, green, red and yellow, is archetypal gaudy regional pride—and it’s a depiction of Lincolnshire space, too; the colours representing the wide expanses of land, sea, sky and crop which make up the county’s landscape. But vast and pastoral—and with limited infrastructure—the region is also haunted by empty space: growing up in Lincolnshire, I was forever reminded of the far more exciting world of culture and civilization beyond the county’s borders.

Lockdown has forced us all to confront the benefits—and limits—of our own spaces. For me, this year has inevitably meant more reading; and being back in Lincolnshire has prompted me to look into the (surprisingly large number) of literary works which depicted the county, its landscapes and unique way of life. In the early months of the pandemic, I trekked over to Somersby, where one of Lincolnshire’s most famous sons, Tennyson, was born—an almost-village, comprising Church and scattering of houses (including Tennyson’s childhood home), and quietly nestled among the undulating Wolds. There’s some Tennysoniana in the Church—Tennyson’s father was the rector of Somersby—but aside from a few posters and leaflets, the area is hardly a place of literary pilgrimage at all.

A glimpse of Tennyson’s childhood home in Somersby.

That’s not to say Somersby didn’t feature in Tennyson’s poetry, however. From ‘The Babbling Brook’, to ‘The Lady of Shallott’ and ‘In Memoriam A. H. H.’, there are glimpses of pastoral landscapes plucked straight from the Lincolnshire environs of Tennyson’s youth. Whenever—pre-coronavirus—I would return home to Lincolnshire from life elsewhere, I’d often think of his ‘Mariana’, too; the depiction of ‘dreary’ routine, ‘glooming flats’ and a ‘moated grange’ just perfectly claustrophobic and dismal Lincolnshire bleakness. But Tennyson also penned a series of poems in Lincolnshire dialect, which I adore. Oft-forgotten by readers and academics alike, the dialect poems capture the vivacious spirit and rhythm of the county; with endearing Lincolnshire characters, rural routines, and a sense of the county’s sweeping topography.

The poems look more daunting than insightful at first glance, though, written with a meticulous eye to phonetic detail—including the use of apostrophes and umlauts to fully replicate the Lincolnshire dialect. Tennyson himself never lost his accent, and in rare wax cylinder recordings of the poet reciting his dialect poems, you can still hear it, broad as the county’s skies. The cadence of Lincolnshire speech has the same lilt and sing-song quality as folk ballads, like ‘The Lincolnshire Poacher’, the unofficial anthem of the county. It’s all rustic, countryside tradition: when, in ‘Northern Farmer: New Style’, Tennyson writes that a farm ‘runs oop’ to the mill, that elongated vowel sound captures both Lincolnshire speech and Lincolnshire space; the breadth of the country’s landscape; the age-old routines and rhythms of the land which roll unbroken from horizon to horizon, past to present.

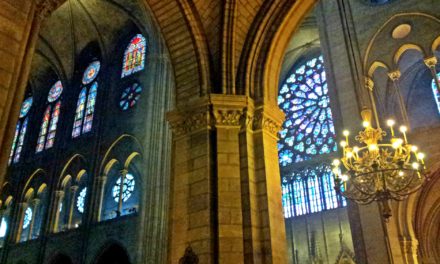

Recently, I’ve been grateful for those spaces. Walking through Lincolnshire, I’ve lapped up the big skies and endless, rolling countryside as far as the eye can see, and felt—more than ever before—lucky to have access to the countryside. But in certain ways, that space has still been tormenting, too. Up on the Wolds, you can often see all the way to the three-towered Lincoln Cathedral, 20-odd miles away. The Cathedral was once the tallest building in the world—a striking sight amid the flat Lincolnshire fens and low Wolds—and glimpsing it, so near and yet so far, has been a constant reminder of the city life and civilization; of access to transport and infrastructure and culture, always available, but always just out of reach.

That vision of the Cathedral looming over the Lincolnshire horizon is also a literary one: DH Lawrence’s The Rainbow has a magnificent description of a journey from Nottinghamshire to visit the building, which sits ‘not far off […] brooding over the town […] in the distance, dark blue lifted watchful in the sky’. References to both distance and elevation in the passage place the Cathedral at the intersection of horizontal and vertical axes of space. The building exists on a pedestal—literally, with its position on Steep Hill, and architectural vastness and significance—but also emotionally, as a magnetic location for the visitor, ‘big […] with all its breadth and ornament’. As Will Brangwen approaches and ‘passed up Steep Hill’, physical space and emotional intensity overlap, with his increasing rapture culminating as he arrives at its front, ‘look[ing] up to the lovely unfolding of the stone’.

Lincoln Cathedral, once the world’s tallest building. (Credit: Edbwilco, CC via Wikimedia)

And, just as the Cathedral encompasses ‘“before” and “after”, folded together’, so too does Lincolnshire, positioned in its own unique space and time, beyond the regular movement of civilisation. Lawrence had experience of the Lincolnshire coast—on a visit to the coastal town of Skegness in winter, I walked past the hotel in which he had stayed to convalesce in the early 1900s, which is now commemorated with a small plaque. This experience of childhood respite spent in Lincolnshire might be why his subsequent depictions of the county emphasise the uniqueness of the Lincolnshire environment as a place of pause, of vacation, or spiritual and emotional fulfilment, separate from everyday life. Another town in Lincolnshire, Mablethorpe—again on the coast—is the setting for another holiday in Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers.

One of Lawrence’s contemporaries, Virginia Woolf, also wrote about Lincolnshire in her novel Night and Day. Here, the county is set in opposition to the crowded skyline, bustle and clamour of London, where ‘the roofs’ stack up into the distance, and where ‘the joint of each paving-stone’ is ‘clearly marked out’ by the endless city light. A few chapters later, the characters take a holiday in Lincolnshire—where, for visitor Ralph Denham, the county is first spied in the dusk, with the ‘dim green’ countryside marked by ‘black trees’ and a twilight which ‘almost hides the body’. The sky might look ‘like a slice of some semilucent stone behind which a lamp burnt’, but here, the modern, electric lights of the city have little use, and are instead ‘obscured’ behind the natural environment, unable to illuminate or clarify the scene.

In contrast to London, Lincolnshire is a place of uncertainty and isolation—‘an entirely different world’, thinks Denham—with its villages lying only ‘somewhere on the rolling piece of cultivated ground in the neighbourhood of Lincoln.’ Characters discuss the limited number of trains to the county and, once in Lincolnshire, struggle to comprehend the county’s geography. Michael Whitworth notes that Woolf herself was more familiar with Norfolk than Lincolnshire—where she initially wanted to set the holiday chapters—with this authorial unreliability contributing to the mystery around Lincolnshire space.

The Lincolnshire portrayed by Woolf is again one of broad, flat, uncanny spaces—‘rumours of the sea’ can be heard from the inland village of Disham—but time is also strangely distended here, with Lincolnshire villagers appearing as if from the Middle Ages. Woolf writes that a stranger speaking to them wouldn’t understand their words—an allusion to the impenetrable Lincolnshire dialect?—whilst the stranger’s voice would have to ‘carry through a hundred years or more before it reached them’. Past and present again overlap here—but this also has a more ominous edge: Woolf describes how Lincolnshire villagers live at ‘the extreme limit of human life’; how walks through the countryside are accompanied by ‘the ghosts of past moods’; how the birds fly, ‘disappearing and returning’ into the night; and how the land of the region is almost swallowed up, ‘lying flat to the very verge of the sky’.

Less than five years after Night and Day was published, cleric and local historian John Charles Cox published a guide to Lincolnshire—with perspectives on the county which, interestingly, show that little has changed in almost 100 years. One of the details Cox mentions are the ‘delightfully wide and extensive views’ in the county—but he also notes popular views of Lincolnshire as a ‘dull, flat plan’, with railways running ‘through the flattest and most dreary district’. Cox particularly draws attention to the ‘low and flat’ coast, noting the history of coastal erosion in Lincolnshire. The county’s flatness is, therefore, also its vulnerability: whilst an aesthetic boon in terms of the area’s vast, pastoral space, flatlands are also treacherous, and open to future destruction.

Steeped in tradition, separated from the present, and sometimes seemingly nothing more than a relic of the past, in Lincolnshire, time runs at an unusual pace. And the county has a rich historical heritage too, particularly from World War II.

In summer, I was sipping cups of coffee with a friend in a local café when a dull, thunderous, rumbling sound began to creep across the sky towards us—the familiar and typically Lincolnshire noise of an Avro Lancaster bomber plane. After a few seconds, the Lancaster itself reared into view: a sluggish, stocky twist of deep-green metal careening above our heads.

Lancaster bomber.

The colossal four-engined Lancaster bombers were used extensively by the Royal Air Force during World War II, deployed for strategic night-time campaigns in Europe. And the wide and flat Lincolnshire countryside became one of the most prominent homes for Lancasters—and for the RAF more generally—during the war.

But bomber ghosts still linger. Among other Lincolnshire-based stories in Jon McGregor’s absorbing 2012 collection This Isn’t the Sort of Thing That Happens to Someone Like You, one tale about a family taking their grandfather back to the airfield where he had been stationed during the war is far from the nostalgic return they’d hoped. The airfield cannot be seen because the ground is ‘so flat’; the grandfather is ‘at a loss’ and doesn’t want to discuss his memories. The grandfather’s experiences of the war—of ‘loading munitions’ and the ‘removal of bodies and body parts’—belong to a separate world; in the present, wartime trauma is hidden away and conflict defused, replaced only by vintage bomber display shows and avid plane fanatics who ‘gaze in awe’. McGregor writes a dark, deeply unsettling Lincolnshire, where the past lingers, and where the land can both hide and reveal sorrow, violence and death.

But it’s not all grim up north. John Betjeman was another writer whose works reflect the unique Lincolnshire way of life, and the intersection between past and present in the county. His ‘A Lincolnshire Tale’ has that same sing-song, folk rhythm as Tennyson, packed with quirky Lincolnshire-esque place-names—‘Kirkby with Muckby-cum-Sparrowby-cum-Spinx’—and depictions of the county’s ‘remoteness’, of properties ‘reverting to marshland again’, and the general unfamiliarity of the region, ‘sinister […] neither fenland nor wold’.

Betjeman knew Lincolnshire better than this, of course, and he travelled much of the area around Lincolnshire, too. In a short 10-minute clip available on the archival BFI Player, with the charming title ‘John Betjeman Goes By Train’, the poet travels from King’s Lynn to Hunstanton, just around the corner of the coast from the county, in Norfolk.

‘Now we are coming out into the open flatland of the mouth of the Wash,’ Betjeman muses in his clipped English accent, ‘flat on all sides—it might be Lincolnshire.’

As Betjeman points out, Lincolnshire-esque countryside—that endless, aching flatness—actually spans beyond the county. Going northwards, there’s slight elevation with the Lincolnshire Wolds, but the level countryside is mostly unbroken until you reach Yorkshire. South, the Fens swirl down, boggy and peaty, from Lincolnshire to Cambridgeshire, Rutland, Norfolk.

When the pandemic restrictions relaxed—somewhat—during the furiously hot weeks of the British summer, Hunstanton was one of the few places outside Lincolnshire to which I tentatively ventured last year. Before tucking into crab sandwiches on the sea-front, I stomped across the Norfolk sands and peered back towards home. On clear days, looking south-east from the Lincolnshire coast, you can sometimes just about pick out a line of solid land—the north Norfolk coastline—in the far distance, jutting between blue-brown sea and blue-grey sky. Like Lawrence’s vision of Lincoln Cathedral, tracking the line back towards the mouth of the Wash is to get a sense of the shape of the English landscape: the sharp angle at which Norfolk projects into the North Sea; the bloated swag of Lincolnshire beyond.

There was no such luck on the Norfolk sands, with Lincolnshire lost in the haze above the summer sea.

Later, in Betjeman’s journey to Hunstanton, he also waxes lyrical about country stations, noting that, ‘deliciously, and unexpectedly, in the shelter there’s a poster, which says: “Come to Bavaria”’.

The irony is that the rail line Betjeman was travelling on was lost in 1969—and it joined many other rail lines in the region which fell to the Beeching Cuts (which led to the closure of thousands of miles of railway lines across the UK) in the late 20th century. Lincolnshire was a victim of the Beeching Cuts too, losing lines which were deemed unprofitable, and leaving many parts of the county cut off from public transport links ever since. In certain ways, Lincolnshire has always existed in permanent lockdown.

Philip Larkin, an adopted son of Hull, a city just north of Lincolnshire, writes marvellously about journeys in and out of the region. His ‘Whitsun Weddings’ depicts the sleepy rail connections between Hull and the wider world: the train is ‘three-quarters-empty’ and ‘late getting away’; its listless speed matching the lack of earnest voyagers on board. An iambic pentameter picks up the pace as the train travels ‘behind’ the houses—but there’s a moment of near-epiphany at the end of the stanza when, after smelling the fish dock, the vista ‘thence’ opens up to the ‘river’s level drifting breadth […] where sky and Lincolnshire and water meet.’ Lincolnshire space is here again associated with expansive landscapes; the county is one solid unit, lodged in its vastness between swathes of sky and river. But this is ‘breadth’, rather than depth: the phrase ‘river’s level’ signals flatness and distance, and as the poem continues—and the train speeds up, grows busier—the reader is reminded of the spaces that must be covered to escape, and the remoteness of the spaces around Lincolnshire.

Lincolnshire.

Hull might be a jumping off point to access other locations, but Lincolnshire acts as foil. Hull, Larkin once said, is ‘in the middle of the lonely country’—and that could stand for Lincolnshire all over. In Larkin’s ‘Here’, detailing a journey back to Hull, the train passes backwards in time from industry to meadows, ‘swerving’ as if unnaturally towards the east, where a large town is a ‘surprise’ to find.

But Larkin also writes more optimistic verse about Lincolnshire—particularly, his ‘Bridge for the Living’, written to commemorate the opening of the Humber Bridge over the river Humber in 1981, which finally consummated the links between Hull and Lincolnshire. From references to the ‘remote’ existence of Hull in the past, the poem suddenly breaks into the present to describe the bridge as a place of energy and connection (‘and now, this stride into our solitude’). Whilst the bridge might be just ‘one plain line’, its expansive properties reach beyond ‘local lives’ to transform and ‘resurrect’ residents’ prospects and the countryside. In fact, writes Larkin, the Humber Bridge includes the ‘dear landscape in a new design’—its dramatic ‘single span’ is a sign that perspectives on the region’s spaces can expand; showing that even in the wasteland, backward region of Lincolnshire/Hull, ‘reaching for the world’ is still possible.

Thinking about bridges is a good way to consider Lincolnshire. The county spans many things, past and present, tradition and modernity, space and isolation; and whilst I doubt it will ever fully shake off its age-old customs or irrefutable remoteness, these traditions do make it a unique place to live—especially for now, whilst the world is still (just about) under lockdown.

Taking a bridge into the county—both physical and literary—is to take a bridge into another world. What matters is that bridges go both ways, too.

Juliette Bretan is a writer and journalist. She has written for The Sunday Times, The New Statesman’s CityMetric, The Independent, Euronews, Ozy, FilmStories, New Eastern Europe, The Calvert Journal and CultureTrip, among others. Currently based in Lincolnshire, she most frequently writes about Poland and Eastern Europe, including culture, history and current affairs. Follow her on Twitter @JCBretan.

Juliette Bretan is a writer and journalist. She has written for The Sunday Times, The New Statesman’s CityMetric, The Independent, Euronews, Ozy, FilmStories, New Eastern Europe, The Calvert Journal and CultureTrip, among others. Currently based in Lincolnshire, she most frequently writes about Poland and Eastern Europe, including culture, history and current affairs. Follow her on Twitter @JCBretan.

[Photo Credits: All photos credited to Juliette Bretan except where indicated.]