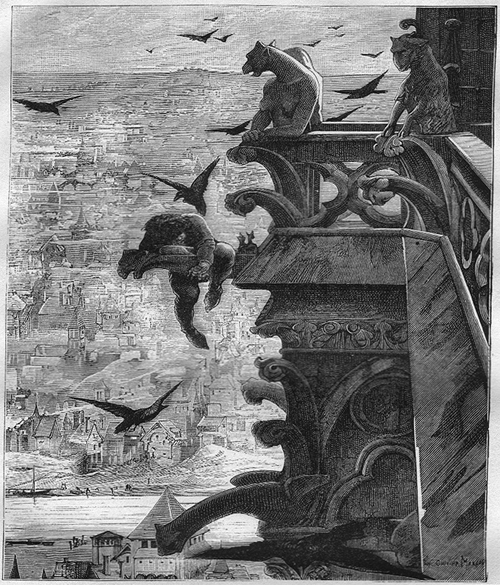

Each face, each stone of the venerable monument, is a page not only of the history of the country, but of the history of science and art as well…Thus, the Roman abbey, the philosophers’ church, the Gothic art, Saxon art, the heavy, round pillar, which recalls Gregory VII, the hermetic symbolism, with which Nicolas Flamel played the prelude to Luther, papal unity, schism, Saint-Germain des Prés, Saint-Jacques de la Boucherie—all are mingled, combined, amalgamated in Notre-Dame. This central mother church is, among the ancient churches of Paris, a sort of chimera; it has the head of one, the limbs of another, the haunches of another, something of all…As the fire’s damage is grieved and assessed and plans for restoration begin, here’s one more of Hugo’s sweeping bird’s-eye views on Notre-Dame de Paris: “Time is the architect, the nation is the builder.” —April 16, 2019 [Header photo credit: Ron Clausen, Creative Commons]They make one feel to what a degree architecture is a primitive thing, by demonstrating (what is also demonstrated by the Cyclopean vestiges, the pyramids of Egypt, the gigantic Hindu pagodas) that the greatest products of architecture are less the works of individuals than of society; rather the offspring of a nation’s effort, than the inspired flash of a man of genius; the deposit left by a whole people; the heaps accumulated by centuries; the residue of successive evaporations of human society—in a word, species of formations. Each wave of time contributes its alluvium, each race deposits its layer on the monument, each individual brings his stone. Thus do the beavers, thus do the bees, thus do men. The great symbol of architecture, Babel, is a hive.

Notre-Dame de Paris: The Chimera, the Hive