My first favorite books were the Oz books, and I was completely obsessed with everything Oz throughout my childhood. So it’s been interesting for me to jump back into that world with my six-year-old son. We recently read The Wizard of Oz together, and I was struck by how it is, first and foremost, almost purely a tale of travel adventure. That it stars a level-headed and optimistic young girl on a quest makes it a rare thing indeed for a book of any era — never mind for the year it was published, 1900.

Dorothy Gale is perhaps the best known, yet least discussed character in American fiction. We take her as part of the landscape, even of our national mythology, yet rarely give her much thought. Probably in large part this is due to the 1939 movie and Judy Garland, who owns the character in our collective pop-cultural consciousness. Garland’s Dorothy is a live wire, and for a Midwestern farm girl, she’s a highly sensitive creature. Unlike in the books, her personality always seems rooted in her emotions. We feel for this Dorothy because her feelings are right there on her skin, thanks to Garland’s quiveringly raw, empathic performance. That her Dorothy always pushes onward despite all that emotion is, I think, why we root for her, and why she is so captivating.

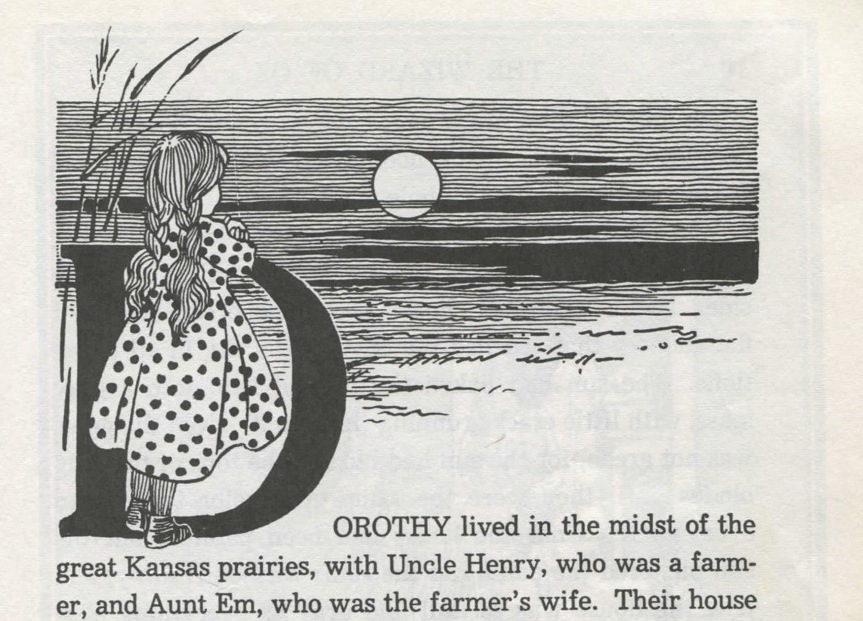

The Dorothy Gale of the books is a different sort of gal, and her story is a lot stranger and more episodic. If anything, the places and beings she encounters in the books are more surreal than what the MGM movie presents, and yet she is never, not once, ruffled. Afraid, excited, delighted, put off —yes. But what so powerfully attracted me to the books, as a girl reader, was how matter-of-fact Dorothy is about her place and her identity in the wildly ever-changing world around her. She never questions whether she is up to the often bizarre task ahead of her. She uses her natural good sense and open-minded nature to befriend, avoid, or vanquish all manner of weird and magical beings. With deadpan, all-American gumption, she keeps easing on down the road.

A note on The Wiz: This much-maligned movie elicits eye-rolls to this day. I can’t speak to the film itself, since I haven’t seen it in its entirety since it arrived in theaters in 1978. But I have always been a shameless fan of the songs. As a kid, I listened to my family’s tape of the movie soundtrack endlessly. The music kills, and Diana Ross, Mabel King, Lena Horne, and Michael Jackson play as much a part in my own experience of Oz as Judy Garland, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke, and Ray Bulger have. This seems to be true for many people in my generation (X)—kids of the 70s who barely remember the movie but grew up with those songs.

But enough of the movies—back to L. Frank Baum’s book. While Oz is so integral to American culture, it’s a terrain that I don’t think we’ve quite figured out. This despite all the allegories that have been attached to The Wizard of Oz, many quite wackadoo. Is the plot a parable of capitalism, the gold standard, or populism? I doubt it’s any of these things.

The story is organically American, and like all great fairy tales pulls from deeper sources. The fact that it is framed as travel adventure—forced travel at that—tugs at deep cultural memories. Especially while reading it to my son, I noticed how effortlessly the book taps into primal notions of home, settlement, displacement, and frontiers—the sort of travel and adventure, often not by choice, that got many of our ancestors here, and then forced them onward. This is the story that The Wizard of Oz and other Oz books reimagine and spin into uniquely American fantasies. And we’re fortunate that L. Frank Baum realized that such a story didn’t just require brave boys to make it work—but also courageous, commonsensical girls.