Icelandic Saga Love Story:

Njal’s Saga and Thingvellir

By Megan Harlan

Once upon a time, I fell in love—headlong, instantaneous love—with the Icelandic sagas. As passion often does, it took me completely by surprise.

For one thing, I knew the sagas as a “type” were all wrong for me: They broke nearly every rule I’d established for my kind of book, by the time I’d enrolled in a Scandinavian Literature course my sophomore year of college. I surely was not a war story kind of person, I believed; nor was I on board with the classic Viking ethos of pillage now, apologize never. But then I opened to the first page of Njal’s Saga—and slid effortlessly into the social scene of southern Iceland a thousand years earlier.

Manuscript page of Njal’s Saga, complete with a true-to-scale illustration of the short but powerful Icelandic horse. (Public Domain via Wikimedia.)

Written around 1280 by an unknown author about events that happened in the 900s, Njal’s Saga—of all the Icelandic sagas—tells the sort of tale that, furthermore, I usually try to avoid: The truly awful violent tragedy where the bad guys win. Njal Thorgeirsson is the tale’s thoughtful and intuitive hero, a lawyer and farmer widely respected for his uncanny foresight and wisdom, and if you get a copy of my Penguin Classics version, you will learn from the back cover’s terse summary that, by the end, Njal and his family will be burnt alive in their home by their enemies.

So there’s that scene to look forward to. But here’s how Njal’s Saga begins:

There was a man called Mord Fiddle, who was the son of Sighvat the Red. Mord was a powerful chieftain, and lived at Voll in the Rangriver Plains. He was also a very experienced lawyer—so skillful, indeed, that no judgement was held to be valid unless he had taken part in it. He had an only daughter called Unn; she was a good-looking, refined, capable girl, and was considered the best match in the Rangriver Plains.

Thus without preamble we find ourselves deposited amid the everyday players of medieval Iceland, being easily introduced to a lawyer and his catch of a daughter, in someplace called Voll. As relationships and predicaments unfold and interlock, we soon notice that the exotic span of a millennia back in time and North Seas island locales we’ve never heard of don’t change human nature—or the human desire for an engrossing, complex, yet forthright story. For these qualities, and for the moving ways it winds existential philosophies of fortune into its characters’ lives, Njal’s Saga is often considered the greatest saga, and among the greatest works of medieval European literature.

And unusual for their era, the Icelandic sagas were all composed in prose, not poetry: Clear-running, powerful, fast-moving prose that sweeps the reader along in a rushing river of narrative. Light on descriptive language and metaphors, the sagas were built for speed—deftly moving across complicated networks of time, family trees, and settings.

In Njal’s Saga, these locations include a wide and often watery array of Icelandic, north Atlantic, and Baltic settlements—characters are forever jumping in their ships and speeding off to brawl in Dublin or plunder in Denmark. There is, for example, the matter-of-factly sex-laden side-trip by Unn’s husband, the warrior Hrut, to Norway, where he encounters a queen who enchants strapping court visitors like himself into her bed—and then won’t let them leave, except under penalty of a doom-fating curse. (Unn, being “capable” indeed, swiftly divorces from Hrut after learning of this interlude.)

A rare contemporaneous depiction of Viking ships: the Bayeux Tapestry circa 1070-1090. (Public Domain via Wikimedia)

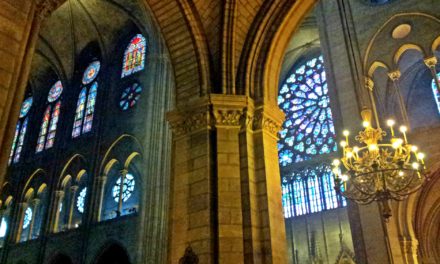

But the center-stage of the story—the setting where much decisive drama occurs at regular intervals—is the Althing: Iceland’s annual open-air assembly, court-of-law, and social gathering. Every midsummer at what is today Thingvellir National Park, Icelanders met to vote on laws, have a party, distribute justice, settle scores, enjoy a reunion, or even find a spouse. Colorful tents were staked, fineries donned, barbecues lit, and everybody schmoozed for two weeks. Only free men could take part in the legal discussions and decisions at the site’s centerpiece, the Law Rock (medieval Scandinavia being no less sexist than anywhere else in Europe), but women often attended as well, though confined to the event’s social sphere.

I’d somehow envisioned the site of the saga-era Althing all wrong: I’d pictured the Law Rock as a single boulder on some desolate lunar plain. (This site in fact hosted the Althing from 930 all the way to 1798; the Icelandic parliament has since relocated to a building 30 miles southwest in Reykjavik, and to which women have been elected since the mid-twentieth century). This is what Thingvellir looks like today—and how it may well have looked in the 900s:

Thingvellir National Park, from the volcanic hillside that includes the Althing’s “Law Rock.” (© Farsickness)

In my defense, Njal’s Saga is, as usual, a little vague on locational descriptions: It was written for people who regularly attended the Althing, so why waste space explaining the scenery? In short, I was not expecting it to be so wildly beautiful. The site is perched at the northern edge of Iceland’s largest natural lake, and on the brilliant day in August 2018 when I explored it, pools and wetlands braided around little islands and jade-green shorelines across the entire sweep of valley: A dazzling interweave of blues, grasslands, and sunlight.

But the volcanic ridge-line on which I stood—a gnarled black rock outcropping—also marks a major geological site: The meeting place of the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates, and the crest of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge formed long ago when the two plates collided.

Where the North American and Eurasian plates meet. (© Farsickness)

It’s fascinating that medieval Icelanders chose this spot, of anywhere on their island, to host their ad-hoc parliament. Did they somehow sense the extreme geological kinesis beneath their feet, the colossal plates that define the Northern Hemisphere rubbing tectonic shoulders in the exact spot where they, as a society, met to shape their own culture? That’s doubtful, of course. But it is a perfect natural stage for people to hold forth—and one considered so culturally valuable it’s deemed a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

From the time Iceland was settled by Norwegian Vikings in 870 to the Althing’s founding in 930, the island’s population had reached 25,000. Today it hovers around 340,000—less than the populations of either Cleveland, Ohio or Arlington, Texas. That’s as stunning to ponder as Iceland’s drama queen topography. So too is a comparison to its nearest island neighbors: At almost 40,000 square miles, Iceland is about 13,000 square miles larger than Ireland—which is today home to more than 4.8 million people.

And while we’re on the subject of the British Isles: “Njal” is pronounced Neal, a name that represents the Gaelic-speaking contingent of the Iceland’s original Celtic and Scandinavian populations (and which happens to be the first name of my proudly Scottish-American father). That’s because Scotland and Ireland were prime sources of slaves, both male and female, for the Icelandic Vikings, who kidnapped and shipped these people back to their island. The Gaelic-speaking slaves intermarried, earned their freedom, and integrated over generations into the larger society—and, I’m guessing, helped to shape Iceland’s extraordinarily creative literary culture.

This culture and its places strike so deeply because of how dramatically they play with our sense of scale: A few hundred Vikings and their slaves becoming a cast of great literary characters three centuries later—immortalized by their own descendants in a very early form of creative nonfiction. A tiny nation that packs nearly the literary wallop of Russia. Panoramic landscapes that resemble various planets in our solar system, yet which somehow, instead of diminishing them, highlight and humanize the individuals moving across them.

Thingvellir. (© Farsickness Journal)