Mosquito

A lyric essay on the writer’s relationship to this most-maligned pest—from the sweltering Winnipeg summers of her childhood to amber beads prized by her Ukrainian immigrant parents.

By Genia Blum

When Winnipeg’s infernal winter finally eases into spring; and the house-high snow dunes shrink into gray hillocks, the last patch of dirt-encrusted ice melts into a slowly evaporating puddle, and the mercury continues its climb; the city transforms into a different kind of hellhole: a pseudo-tropical purgatory where sunstroke can kill you, if the insects don’t devour you first.

Heat lines gyrate in the distance, asphalt roads soften into rivers of black licorice; the cracked concrete sidewalks, damaged in a cycle of freeze and thaw, become hot enough to fry eggs; and while water sprinklers tick-tick all day, the sun will still scorch every blade of grass on your lawn. As the ball of fire descends into the red horizon, and thunderhead clouds roll in for a brief storm, you may be lured outdoors by a promise of coolness. But this is the hour of the mosquito, whose bloodthirsty cohort emerges at dusk, ravenous from hiding all day between the yew and forsythia bushes, your mother’s drought-resistant perennials, and the tall grass at the edge of the lawn your father didn’t bother to cut. Undeterred by the long cotton dress you thought would protect your limbs, the first buzzing female alights. She pierces your skin with the tip of her straw-like mouth, injects anticoagulant to more easily guzzle your blood and—if you don’t clobber her first—bloats her belly until it resembles a Burmese ruby. More and more members of the squadron attack and, alerted by their hum, you begin to swat: flattening the swarming pests, splattering your own blood. Every sting leaves behind a throbbing, itchy bump, and you’ll accumulate so many in the course of the summer that you’ll be scratching straight into fall.

When I was growing up in Winnipeg, insect-borne diseases weren’t a concern, but bites and stings were, and bug repellent was considered more important than sun protection. It was accepted that children would blister and peel in the summer, and my sister and I were barely encouraged to wear sun hats; but every square inch of our skin was coated with a greasy chemical concoction called OFF! that was sold at the drugstore in either a bottle or an aerosol can. My mother layered the contents of both on our bodies, for a protective effect that lasted no more than an hour, although the foul odor hung around until bath time.

“Keep your windows shut tonight,” my father would instruct us before we went to bed because, in the early morning hours, a repurposed Douglas DC-3 with insecticide-filled tanks would fly loud and low over our house, spraying every neighborhood on both sides of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. Sometimes, out of sight of our parents, we’d follow fogging trucks down streets and alleys, running through toxic, billowing DDT clouds for fun. The powerful chemical compound eliminated malaria in Europe, but hardly affected Winnipeg’s mosquito population.

DDT was later banned, but it’s still used in countries where malaria is endemic—like the Dominican Republic, where a prehistoric mosquito carrying a malarial parasite was found preserved in a lump of ancient amber. The insect’s oldest forbear, however, was discovered just north of Winnipeg, trapped in the fossilized resin of an extinct tree species from the days when dinosaurs still roamed the earth. Other specimens have turned up in amber washed ashore on the coast of the Baltic Sea, gemstones so cherished by my Ukrainian parents that, on my sixteenth birthday—a milestone when school friends received keys to their own cars—I was presented with a waist-long, glossy necklace imported from what was then communist Poland.

Although our windows had mesh screens, we kept them closed during the day because of the heat. Without air-conditioning, we escaped to the damp cold of the basement recreation room, where we played games, read, watched TV, squabbled and brawled when we got bored. On weekends, our family would cool off in Lake Winnipeg, an hour’s drive from the city. My sister and I favored Grand Beach with its magnificent white sand dunes and a boardwalk with cotton candy and hot dog stands. My immigrant parents, however, preferred a swimming spot on the opposite shore that belonged to the Ukrainian Catholic Church, but was actually ruled by a mob of mosquitos who ceded sovereignty only on a narrow strip of lakeshore, to a horde of flesh-eating horseflies. Ukrainian Park had little infrastructure in those days: several primitive cabins, some outhouses, and a rustic, Carpathian-style wooden church. My father would park his Oldsmobile Super 88 near a stand of scrawny birch trees and, even before my sister and I made a move to get out, my mother would yell, “Run, quick, run!”—and we’d dash to the shoreline through an unmown, mosquito-infested meadow, burning the soles of our feet when we reached the sand, hopping over vicious horseflies, jumping straight into the lake. You were really only safe in the water.

With its vast, blue-green expanse, Lake Winnipeg resembles an ocean. Squinting against the sun, I’d shield my eyes with my hands and try to make out the opposite shore, always indiscernible.

While my sister and I splashed around in the water, my father cracked open a bottle of Molson’s and set off for a walk. A fading chain of footprints followed him in the wet silt. My mother settled into a foldable lounger with a bobbing, adjustable parasol. Behind her stylish sunglasses, she never once took her eyes off us.

The beach could have been a desert island, if only coconut palms had grown in its sand. Suspended under the golden sun, submerged up to my chest, the rest of me baked in the heat. I went in deeper, until the water reached my chin. My mother sat up and waved at me to return.

But the lake was still and shallow; and the mosquitoes were hiding in the scrub.

They wouldn’t start biting until sunset.

Genia Blum is a Swiss Ukrainian Canadian writer, translator, and dancer. Her work has been anthologized, published widely in literary journals, and received numerous Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net nominations. “Slaves of Dance,” based on excerpts from her memoir in progress, was named a “Notable” in The Best American Essays 2019. Find @geniablum on Twitter and Instagram or visit her website: www.geniablum.com.

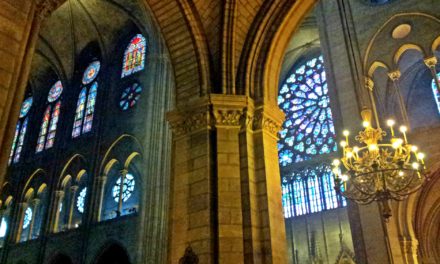

[Header image credit: Tris_T7, Wikimedia Commons]