My Lost L.A.

An essay about falling in love with the early ’80s punk and music scene in Los Angeles—where the writer (above left) moved through the subculture and a stage of life.

By Mari L’Esperance

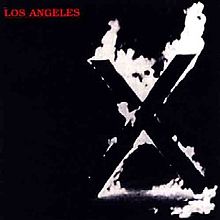

On a witheringly hot summer day in 1981, my childhood friend Deena and I were riding along in her then-husband’s car in the Pomona Valley, heat blasting through the rolled-down windows. “You haven’t heard of X?!?,” she said to me, incredulous, popping the band’s 1980 debut release Los Angeles into the cassette player. “You’ve gotta hear this — it’ll blow your mind!” Seconds later, Billy Zoom’s opening guitar riff to the titular track cut through the thick valley heat like a saw blade. In that moment, I passed through an initiatory gate.

* * *

Looking to the past is not only about nostalgia, that much-maligned compulsion to pine for what’s irretrievable. From a developmental perspective, revisiting one’s past in a meaningful way can be healing, and integrative. Parts of the self that had been lost to traumatic disruptions and the urgencies of survival can be reclaimed and understood, allowing one to move forward.

I’ve long been interested in how experiences shape a person, determine their choices — those made and not made. In this light, my ‘80s L.A. story is one of many chapters in a peripatetic life, but a formative and significant one. I’d not given it much serious thought for a long time, but late in the pandemic the memories came roaring back — partly due to age, but also, I suspect, because that particular chapter had long been muted by time, the weight of unforeseen adult responsibilities, and intervening personal losses.

Recently I re-watched The Decline of Western Civilization for the first time in over 20 years. Penelope Spheeris’s 1981 film documented the early L.A. punk rock scene and features performances by X, Black Flag, Fear, the Germs, and the Circle Jerks, among others. The film brought back the music and feeling of that lost world — a heady mix of youthful rebellion, apathy, rage, disgust with the status quo, and (perhaps most importantly for me) something akin to euphoria.

* * *

“So, dude, what about this L.A. scene?

“Don’t know, man, it just happened.”

—Claude Bessy, from Make the Music Go Bang: The Early L.A. Punk Scene

L.A. in the ‘70s and ‘80s was gritty. Crime was rampant, air pollution made it hard to breathe on bad days (the California Clean Air Act didn’t become law until 1988), manufacturing jobs were disappearing, crack cocaine and violent gangs overran some neighborhoods, and parts of the city were derelict, including Hollywood and downtown. In South Central, where I lived for a brief while, police helicopters circled at all hours of day and night, strafing darkened windows and alleyways with powerful search beams. To top it off, Ronald Reagan took office as president in January 1981.

But L.A. was also a city where ordinary working people could still afford a modest home. “Old man” dive bars that opened at the crack of dawn, thrift stores, classic midcentury coffee shops like Ben Frank’s and Norm’s, and record stores were plentiful. One could rent a cheap apartment in Hollywood with roommates, work a dumb job to pay expenses, and have money left over to hear live music a few nights a week, even to buy an old beater for driving around town.

“The original punk scene was basically a bunch of misfits and people who just couldn’t seem to fit into society, most of them. There were also a few well-off, normal people who were trying to be punk because they thought it was cool. But most of us legitimately couldn’t function any higher than that.” —Billy Zoom of X, glidemagazine.com, August 24, 2020

Out of this confluence emerged a cacophony of DIY music, experimental art and performance, and spoken word that we’ll probably not see the likes of again. It was a “perfect storm” that birthed a movement, or a web of interconnected movements, that would be impossible to replicate in today’s climate. Disenfranchised and bored young people, many the products of broken homes and soulless suburbs, latchkey kids and squatters and runaways living on the streets of Hollywood, flocked to hear live music, drink, score drugs, and let off steam at venues like the Masque, Florentine Gardens, Cathay de Grande, Anti Club, Club 88, and Madame Wong’s East. Many were young, white, and male, but there were women, too… and, being that it was L.A., there were Blacks, Latinos, some Asians, and a range of ages in the mix. You could drink if you looked old enough and venues were often crowded way beyond what city fire codes permitted. The words “cover charge,” if there was one, meant five bucks or a couple of Budweisers. Many shows got shut down by law enforcement for capacity violations, underage drinking, violent clashes, or all three, making it harder for bands to find receptive venues. Spheeris’s film, and Don Snowden’s and Gary Leonard’s 1997 book Make the Music Go Bang: The Early L.A. Punk Scene, documented that world in images and the words of those who lived it.

* * *

It is an understatement to say that I am forever “late to the party.” I grew up highly mobile in Southern California, Guam, and Japan, the daughter of an immigrant Japanese mother and a French Canadian-New Englander father. By the time I’d enrolled in college in the South Bay city of Long Beach in 1979, I’d lived in 15 different dwellings. Frequent moves and school changes (three high schools, each separated by an ocean) made it challenging to keep up with my peer groups and their preoccupations of the moment. A perennial outsider, I longed to fit in, but didn’t know the first thing about where or how to begin.

By the time I first heard X, on that hot day in the Pomona Valley, L.A.’s “old guard” punk rock scene had plateaued and was morphing into other forms. The music of that era arrived in my life like a comet; it was white heat, and feral — all embodied, undifferentiated feeling. I’d never before felt that kind of intensity for anything, ever — I was utterly besotted, and let myself be swept along. At 20, it was the first time I’d felt truly passionate about something — more importantly, something that hadn’t been imposed upon me by adults (as had ten years of piano lessons). In college I was a half-hearted journalism major, encouraged by my well-intentioned immigrant mother to study something “useful.” I started listening to KROQ, which was the voice of L.A.’s punk rock and New Wave scenes, as well as KLOS and KMET, both of which broadcast AOR (Album Oriented Rock) like Van Halen and Ozzy Osbourne and, late at night, bands out of L.A.’s burgeoning metal scene, including Ratt, Dokken, and Mötley Crüe, who’d go on to spawn a slew of copycats.

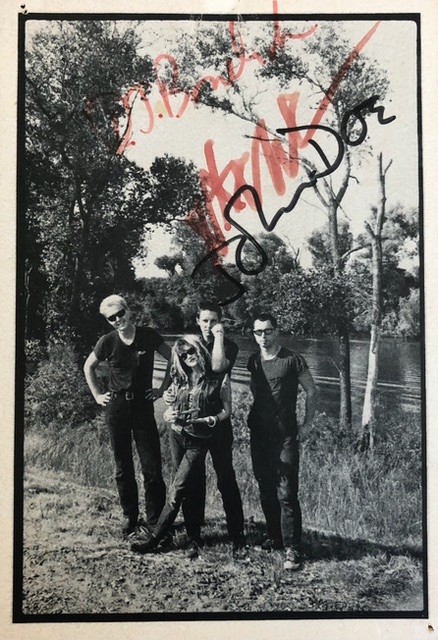

I frequented local record stores and estate shops in then-decrepit downtown Long Beach, riding my bike from Belmont Shore along bucolic First Street with its mature trees and large Craftsman homes. Exene Cervenka, X’s co-vocalist with then-husband John Doe, was my muse — I wanted to be her, look like her, write like her. Exene was everything that I wasn’t: edgy, creative, fearless, irreverent, and visually arresting in her mismatched thrift-store dresses and cardigans, bangle-covered arms, and darkly outlined eyes and rouged lips. I couldn’t take my eyes off her.

the author’s autographed 1983 postcard of X: Billy Zoom, Exene Cervenka, John Doe, DJ Bonebrake (photo credit: Michael Hyatt)

* * *

During this time, I got it into my head that I wanted to work in the music business. A job at a record company sounded terribly exciting, and, as the daughter of a musician father, I wanted to be around music (perhaps to feel closer to him). I studiously pored over issues of Billboard and Variety, avidly followed news of promotions and power moves. But I was stuck in Long Beach with zero connections, and was a terrible networker. Furthermore, I had no idea what I wanted to do, and no plan. I needed an in.

In my senior year, still waitressing to support myself, I somehow heard about, and applied for, a part-time unpaid internship at a music magazine in Hollywood. Likely because no one else wanted to work for free, I got it. The magazine occupied offices in a nondescript commercial building on Sunset Boulevard, across the street from Crossroads of the World. That stretch of Sunset, a couple of blocks east of North Highland, was seedy then — winos lay passed out on the sidewalk and sex workers plied their trade outside our front door, dressed to the nines (our advertising manager, a fan of local metal bands and a frequenter of the Troubadour where many of them performed, often consulted the ladies on the street for fashion tips: “Girl!… I got these boots at Frederick’s of Hollywood!!”). Later, in anticipation of the ‘84 Olympics, they were all summarily cleared out.

As an editorial intern, I wrote the occasional article about, and conducted the even rarer interview with, local bands — nothing noteworthy — but was largely relegated to proofreading and grunt tasks. The magazine’s creative department, which depended on the contributions of unpaid and underpaid freelance writers and photographers, was a smart, ragtag bunch. I was young and green… and I learned.

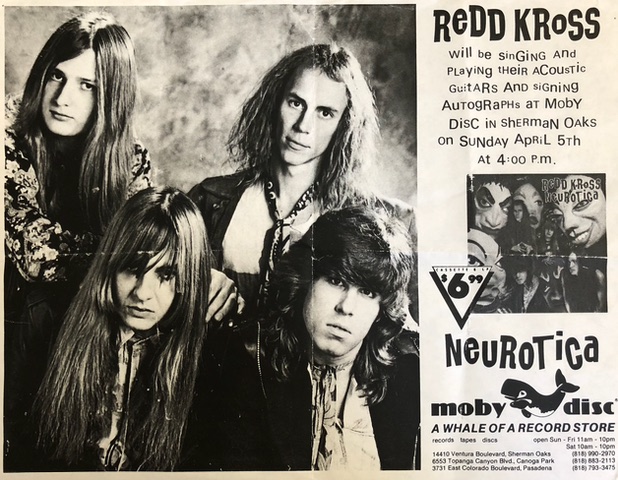

I commuted to Hollywood from Long Beach, listening to KROQ and cassettes on my boombox, as my old car lacked a functioning radio. It didn’t take me long to realize that I’d likely make a terrible journalist (not gutsy enough). But I had the good fortune to meet Wendy, a recent art school graduate and an avid clubgoer and music fan who toiled in the art department (“art slave,” as she called herself). Wendy was a native Angeleno who’d grown up in the Valley. She seemed to know everything about L.A., and I knew practically nothing. Wendy schooled me in the city’s music history that I’d missed: late ‘70s gigs at the Starwood (Quiet Riot with Randy Rhoads! the Go-Go’s! the Runaways!); early punk rock at the Masque and the Anti Club; teenage shenanigans at the Sugar Shack, an all-ages dance club in the Valley… and more. I’m pretty sure I first saw Fast Times at Ridgemont High, This is Spinal Tap, and Repo Man with her during this period. Wendy also introduced me to Moby Disc Records in Sherman Oaks, where I spent many happy hours riffling through the bins.

* * *

A few months after I graduated at the end of ’83, I left my waitressing job in Long Beach and moved into a shared rented house in North Hollywood that I’d found through The Recycler, a free classifieds circular. My two female roommates turned out to be Van Halen’s former costume designer, and Jacquie, who worked at a prominent music publishing company housed in the penthouse of the 9000 Building on the Sunset Strip, across the street from the legendary Rainbow Bar & Grill, Roxy Theatre, and Gazzarri’s. Jacquie hooked me up with a position as a “professional assistant” in the master tape (yup, that’s reel-to-reel) library at her company. I wasn’t particularly interested in music publishing, and the job wasn’t the glamorous record company gig I’d fantasized about… but it (barely) paid the rent and I figured I’d learn a thing or two about the business. I was paid $250 a week, before taxes, and commuted over Laurel Canyon from the Valley in my periodically overheating Datsun B-210 (with black vinyl interior and no A/C). One of my job perks entailed making regular shopping trips to Sunset Tower Records down the street, which, like so much else in that area, no longer exists. Eventually I migrated to the copyright department, which paid a bit more, and where I sat in a cubicle all day in front of a Wang computer, researching copyright permissions. My attempts to find another industry job were fruitless.

Meanwhile, the original L.A. punk scene had splintered off into hardcore, New Wave, glam metal, roots music-inspired cowpunk, the Paisley Underground’s neo-psychedelia, and other styles and sensibilities. I was interested in all of it, except for the hardcore shows — that level of testosterone-fueled aggression scared me. Every week I scoured the L.A. Weekly’s club listings. There was no social media, so club promoters and bands took out ads in local papers or distributed fliers everywhere. Over the course of a couple of years, I saw many local bands perform — including X, Redd Kross, the mighty Channel 3, Dickies, Los Lobos, Blasters, Minutemen, Suburban Lawns, Bangs — at venues like the Troubadour, Whisky a Go Go, Music Machine, Madame Wong’s West, Hong Kong Café, Club Lingerie (Brendan Mullen’s successful follow-up to the defunct Masque), Al’s Bar downtown, and Wolf & Rissmiller’s Country Club in Reseda. In those days it wasn’t unusual for a variety of acts to be featured on the same bill… so in one night you might get Phranc (lesbian acoustic folk), Tex & the Horseheads (punk rock), the Screamin’ Sirens (all-female punk-rockabilly), and a performance artist like Johanna Went. They’d all risen out of the same eclectic mash. This hybridity appealed to my hybrid self, although I would not make the connection for years.

* * *

By ’85 I’d begun to feel like I was coming to the end of something, and my corporate desk job had no meaning. Glam metal now ruled the Strip, MTV was the new cool kid in town, and on weekend nights the sidewalks in front of popular clubs swarmed with women and men, indistinguishable in haystack hairdos, leather, and spandex. Live music of all kinds still thrived in venues around the city, but the anarchist DIY spirit and energy of previous years had dispersed, replaced by ‘80s decadence for decadence’s sake. My world of misfits, where I’d almost felt at home, was no more. Music would continue to be an important part of my life, but it had changed. I had changed. It was time to push off.

Mari L’Esperance was born in Kobe, Japan and raised in Southern California, Guam, and Japan. A graduate of New York University’s Creative Writing Program, L’Esperance is the author of The Darkened Temple (awarded a Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry and published by University of Nebraska Press) and co-editor (with Tomás Q. Morín) of Coming Close: Forty Essays on Philip Levine (published by Prairie Lights Books/University of Iowa Press). Most recently, her work has appeared in They Rise Like a Wave: An Anthology of Asian American Women Poets (2022 Blue Oak Press). Her poetry chapbook Begin Here was awarded a Sarasota Poetry Theatre Press Chapbook Prize. L’Esperance currently lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and can be found online at www.marilesperance.com.

[Header photo credit: unknown. Mari L’Esperance (L) and Amy, then married to Dennis Duck of the Dream Syndicate, at a private party in the San Fernando Valley, 1984.]