Travels to Dostoevsky’s Central Asian Home

A writer explores his time in eastern Kazakhstan—meeting place of Russia and Central Asia—where Dostoevsky once served in the Czar’s army, wrote several early works, and left a legacy still felt today.

By Andrew Yim

In December 1994, I set out from Almaty, the capital at the time, for the cities of northeast Kazakhstan, Ust-Kamenogorsk and Semipalatinsk (now known as Semey). The trip was ostensibly to recruit candidates for a student exchange administered by my employer, The American Collegiate Consortium. But I also knew that Dostoevsky lived for several years in Semipalatinsk. So the trip to northeast Kazakhstan, where Russia and Central Asia meet and mix, was also an opportunity to explore this period of Dostoevsky’s life and works.

***

Dostoevsky’s journey to Semipalatinsk started on December 22, 1849, when, just moments before execution by firing squad for supposed anti-government activity, he was pardoned by the czar and instead banished to a prison colony in Omsk, a regional center in southwestern Siberia. After four years in shackles, “constantly under surveillance,” and “without a creature to whom I could open my heart,” he was given reprieve. Instead of prison, he was sent to serve in the Czar’s army in Semipalatinsk, a large town at the edge of the “Kyrgyz Steppe,” where the Russian Empire met the nomads of Central Asia.

The four years in prison, before his exile to Semipalatinsk, were as formative as they were brutal. Expelled from St. Petersburg literary society to hard labor in Siberia, he felt like “a slice cut from a loaf, or a person buried underground.” He arrived in Semipalatinsk physically and emotionally broken. He writes that after four years in captivity, he had become “a block of wood.” As he struggled to recover and begin to write, he also grieved the loss of precious years of creativity and the sense that “everything is spoilt for me.”

Though located in Central Asia, Semipalatinsk was in some ways similar to Omsk. He described these towns in the first paragraph of The House of the Dead, which he began to write while in Semipalatinsk. Located “in the midst of steppes, mountains and impassable forests,” they were “wretched little towns of one or at the most two thousand inhabitants, with two churches, one in the town and one in the cemetery.”

***

In modern times, Semipalatinsk was transformed from a sleepy border town to a key hub in the Soviet military-industrial complex. From 1949 to 1989, at “The Polygon,” a nuclear test site 80 miles west of Semipalatinsk, the Soviets conducted 465 above and then below ground nuclear weapons tests. For decades, nuclear clouds drifted over pastures and fields farmed by Kazaks and Uyghurs. In addition to the Polygon, the region contained mines and refineries for various metals, including lead and beryllium. In September 1989, a beryllium factory in Ust-Kamenogorsk exploded, sending radioactive pollutants into air and water.

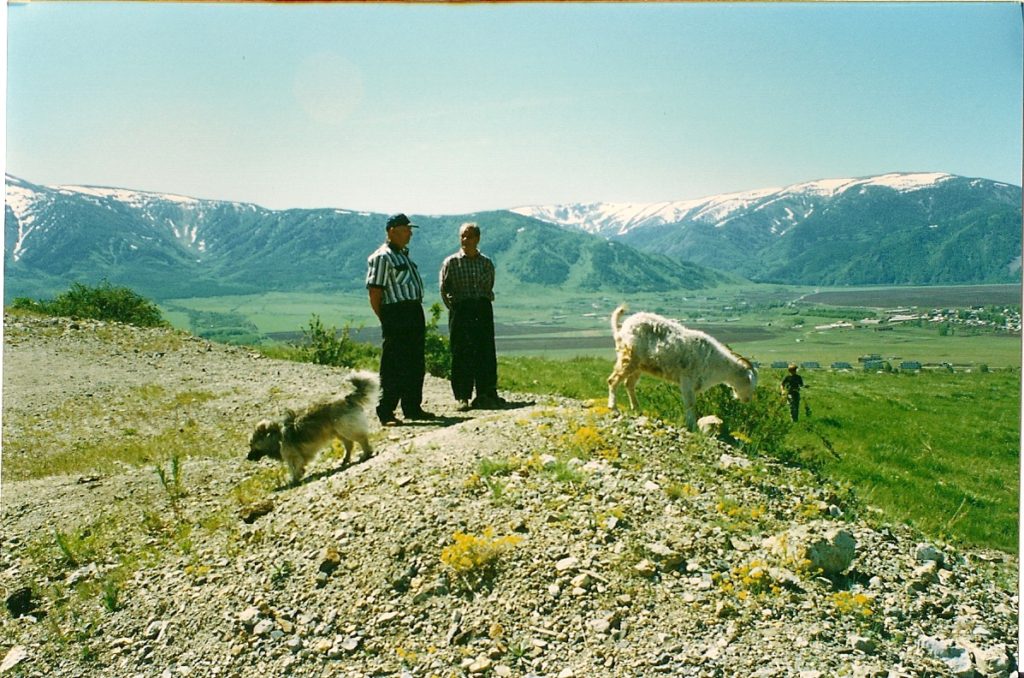

The two images of Semipalatinsk, Dostoevsky then Polygon, were on my mind as I boarded the bus from Ust-Kamenogorsk to Semipalatinsk. The urban sprawl of Ust-Kamenogorsk, clusters of apartment buildings, street side markets, and factories, gave way to quarter acre dachas and then steppe. During a smoke break, I struck up a conversation with a Kazak veterinarian who taught at Semipalatinsk State University. He was returning from the birthday party of a childhood friend, which included a trip to the banya, with drinks, toasts, and snacks between sweat sessions with birch branches.

For the next three hours we moved between silence and light conversation as the fields and villages of northeast Kazakhstan passed under overcast skies and drizzle. As we approached city limits, he asked me where I planned to stay in Semipalatinsk. I was headed for the Semey Hotel near the center square, I told him. To my chagrin, he replied that, without a special visa, Semipalatinsk was still a closed city to foreigners. The hotel wouldn’t let me check in without a special visa. A remnant of Soviet law, some cities were still “closed” if they had factories or institutions deemed vital to national security. I felt a surge of adrenaline until he told me not to worry. He assured me that he’d use his passport to check me into the hotel.

***

Dostoevsky’s letters from Semipalatinsk reflect a man in a hurry to make the most of his second chance at life. He hustles friends and family for cash (“I need money…I want money”), books (“But still I have no books, not even necessary ones, at hand, and time is going by”), and release from military service (“I am asking only the possibility of giving up the military, and entering the civil service”). Despite four years of prison life, he is still an urbane writer, jockeying for position in the literary hierarchy. He has sharp words for rivals (“Do you really think Pissensky’s novel excellent? It is mediocre work”), as he negotiates contracts and projects (“Why do I, then, in my need, allow myself to get only 100 rubles a sheet”). And then, he falls in love (“So very much had I grown to you…when I no longer have you near me, I begin to understand many things”) with Maria Dmitrievna Isaeva, who will become his first wife.

Given the depravation, desolation, and cruelty of the preceding years, his first work in Semipalatinsk, the novella Uncle’s Dream, is a curiously light, almost vaudevillian piece. The queen bee of a provincial town, Marina Alexandrova Moskaleva, schemes to marry her daughter off to an old, wealthy general. The narrator, a Dostoevskian Bridget Jones or Whistledown, writes like a back page gossip columnist as he, or she, describes social climbers and restless dreamers with sharp observations and cutting asides. The relentless, shameless striving to move up in society, out of the provinces to St. Petersburg, resemble Dostoevsky’s own petitions to friends and contacts for assistance in return to European Russia.

Near the end of the burlesque the story takes a strange turn. Falling prey to Marina Alexandrovna’s clever machinations and manipulations, the general proposes to her daughter Zina. But in regret, the next day he disavows the proposal. It was, he exclaims, all a dream, “I assure you, you are under a delusion: it was a dream.” He urges them to accept that their memories were but a figment of his dream. If it was all a dream, then, ipso facto, he had not proposed to Zina. History and memory vanish into thin air.

***

I lurked at the far side of the reception as the veterinarian checked into the hotel, then surreptitiously followed him to the room. I was in a double, he told me, with a roommate. In the Soviet times, solitary travelers were often assigned roommates. In some places, the practice persisted. My roommate, a middle-aged man with briefcase full of forms and ledgers, greeted us with a calm smile and strong handshake. He nodded his head in understanding as the veterinarian explained the situation. After the veterinarian left, we decided to take a walk around Semipalatinsk.

My roommate, I learned as we strolled past utilitarian Soviet and then faded, St. Petersburg rococo architecture, was a German-Russian, descended from Germans imported by the czars to build imperial Russia’s factories and infrastructure. A slim, compact man with a military presence, he was a traveling salesman for an Indian tea company. I mentioned the Dostoevsky Museum in Semipalatinsk and he agreed to visit.

Walking to the museum, I strained to see or feel Dostoevsky’s Semipalatinsk. A few small houses had survived the decades. Their weathered eaves and gates of birch and pine were cut in the Slavic style, with soft curves and whimsical ornamentation. The museum itself, the house where Dostoevsky lived, was built in a similar, modest style. But in the shadow of homogenous apartment buildings and facades, the scent of his world was distant.

Unfortunately, we arrived after closing time. There would be no chance to commune with Dostoevsky in the room where he wrote The House of the Dead. Instead, we inspected a bronze statue of Dostoevsky sitting next to Shoquan Valikhanov, a Kazak ethnographer who befriended him in Semipalatinsk. I couldn’t help but sense a certain Soviet sensibility in the inscription, which described the relationship as “a wonderful witness to the historical friendship between the Kazak and Russian Peoples.”

We returned to the hotel and then dinner with too much cheap vodka. I woke the next morning to two policeman standing by my bed, asking for my passport. The front desk had figured out that an unauthorized American was at the hotel and called the police. I desperately looked to my roommate for help. He took them aside and negotiated a “fine” to settle the matter.

***

During his time in Semipalatinsk, Dostoevsky knew he was not ready, spiritually, emotionally and perhaps even physically, to write a true novel (“I have done some work, but the carrying out of my chef d’oeuvre I have postponed. For that I need to be in a more tranquil mind”). But the two other pieces he wrote while in Semipalatinsk seem a transition from prisoner, stripped of voice and autonomy, back to writer. The House of the Dead is essentially a journalistic, even anthropological, effort, describing life in the prison camp. He was fascinated and then repulsed by life in prison (“back-biting, intrigues, slander, envy, quarreling, hatred were always conspicuous in this hellish life”). The House of the Dead brims with Dostoevsky’s pithy observations on the behaviors and psychology of prisoners and guards, who likely provided rich material for his later novels.

Like Dostoevsky, the narrator in Village of Stepanchikovo comes from St. Petersburg to the provinces, at once observer and then, as the story unfolds, participant. He finds that Foma Fomich Opiskin, a writer purportedly from Moscow, has, like a Svengali or Rasputin, managed to gain great influence over his grandmother and uncle. With shame and humiliation as his primary tools, he begins to control their thoughts and actions. At times farce and then satire, the novel ends with violence and then reconciliation as the narrator’s uncle at first rebels against and then submits to Opiskin’s demands and expectations. The Karamazovs and Raskolnikov seem to be hiding in the shadows, waiting for entrance.

***

One year later, now employed by an American NGO supporting local environmentalists, I returned to northeast Kazakstan to meet with activists. Sergei Shafarenko, a teacher and “deep ecologist” with a hypnotic presence, hosted me in Ust Kamenogorsk. He showed me his studio, where students and colleagues edited films on the ecology of the region. The films, he said, would help to heal the people and their environment. The memory of the radioactive explosion from the beryllium factory was still raw.

The next day I traveled to Leninogorsk, a town 60 miles east, where a few pensioners were documenting pollution from a lead mine and refinery. The owners, they claimed, deposited waste from the mine and refinery in open pits throughout the town, which then seeped into soil and water. They showed me the various piles of waste on the outskirts of town. Bureaucrats survived on bribes from the factory and so were loath to fine or punish the owners. Neither the rugged landscape nor stubborn bureaucrats had changed much since Dostoevsky’s time.

It was a world and time far away from Uncle’s Dream, The House of the Dead, and Village of Stepanchikovo. But in retrospect, I realize the connection I sought with Dostoevsky was in the words and lives of those I met and even befriended. His world was alive in the veterinarian, who secured a hotel room for me without expectation of reward, and Sergei Shafarenko, a spiritual idealist who hoped to reconnect us to the natural world. One hundred and forty years later, between steppe, mountain and forest, the same rich tapestry of Dostoevsky’s world, the poets, dreamers, saints, strivers, schemers, egoists, and thieves, still flourished.

Andrew Yim is a writer, traveler, and, during the weekdays and occasional Saturday morning, primary care nurse practitioner. A Russian Studies major as an undergrad, he lived and worked in Moscow, Russia and Almaty, Kazakhstan from 1994 to 1998. His essays have appeared in The New York Times, The New Haven Review, Trail Runner Magazine, and others.

Further Reading/Sources:

- Letters of Fyodor Michailovitch Dostoevsky to His Family and Friends. Translated by Ethel Colburn Mayne. London: Chatto and Windus, 1914.

- “4 June (1855): Fyodor Dosteovsky to Maria Dmitreievna Isaeva.” This Day in Letters: The American Reader.