Andalucia

by Andrew and Suzanne Edwards (I.B. Taurus, $25)

Reviewed by Nina Lewallen Hufford

Now that we all travel with smartphones—with Google maps, Yelp, Trip Advisor, and Expedia at our fingertips—heavy, text-driven guidebooks seem obsolete. But what these helpful apps cannot do is add texture and depth to our travels, to reveal the rich history of a region and let us walk in the footsteps of authors who have captured some of its essence. That is the promise of

I. B. Taurus’s Literary Guides for Travelers series, which aims to “celebrate the spirit of place through the experiences of history’s greatest writers, artists and travelers.”

Attractive, compact hardbacks filled with dense prose, the books in this series are designed to be read before a trip, to deepen the pre-vacation anticipation that recent studies have shown is really the most rewarding aspect of travel.

This new volume by Andrew and Suzanne Edwards, authors of a previous book in the series on Sicily, tackles southern Spain. Each chapter of

Andalucia focuses on a different province, keyed to a helpful map. The introduction explains the authors’ admirable goal of including local voices, not just the observations of Anglo travelers on the Grand Tour, and their struggle to reveal the true heart of Andalucia while avoiding “hackneyed” stereotypes of bullfighting or flamenco guitars or “the intensity of a lover’s revenge.”

The authors of

Andalucia dutifully enumerate the literary figures associated with each province. In the first chapter, devoted to Seville, they discuss a range of authors, from Lord Byron, Miguel de Cervantes, Théophile Gautier, and Washington Irving to the lesser-known Henry Swinburne (a Brit who traveled to Seville in the 1770s), the “idiosyncratic Englishman” and missionary (of a sort) George Borrow, Spanish writer Luis Cernuda of the Generation of ’27, and contemporary crime writer Robert Wilson. (An appendix with author profiles as well as a useful chronology linking literary/cultural events to political events are included at the end of the volume.)

While we learn a bit about each writer, and his connection to Seville (they are all men, in this chapter), we are rarely offered the opportunity to view the city through their eyes. Direct quotes are few and far between. When the Edwardses have been able to include pertinent descriptions, they are often less than enlightening. What does Swinburne have to say about the famous Seville bell tower, which he visited in 1775? “At one angle stands the Giralda, or belfry, a tower 350 feet high, and 50 square [. . . ] the Christians have added two stories and a prodigious weathercock.”

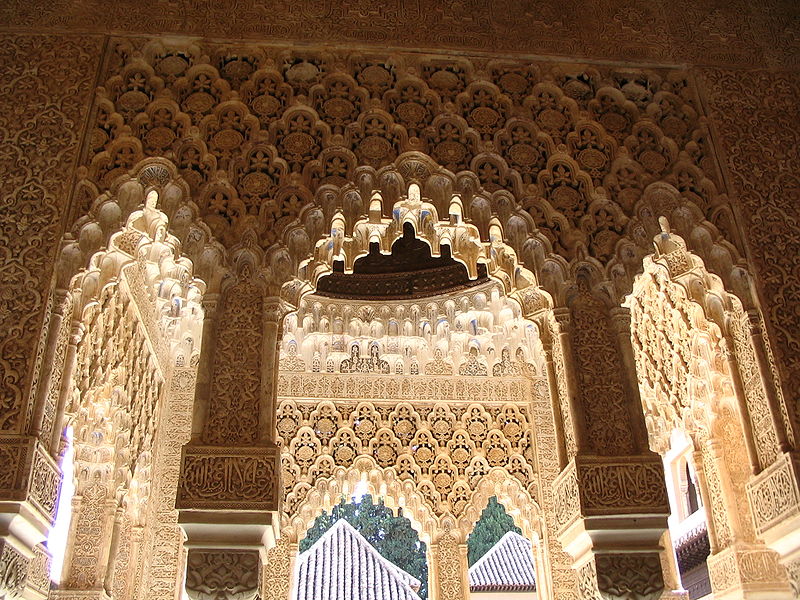

I was especially looking forward to the chapter on Granada, home to perhaps my favorite building in the world, the Moorish Alhambra palace and its gardens. The Edwardses have more to work with in this chapter: Federico García Lorca looms large over the section of the chapter devoted to the city itself. Excerpts from Lorca’s

Sketches of Spain (1918) amply provide the poetic sense of place promised by the series: “Shadows slip over the bonfire that is the Alhambra . . . The Vega [plain] lies flat and silent.” We are led through Lorca’s city: the site of his family’s residences, the location of a café where he hung out with his literary circle, his college residence hall, his family’s summer house outside the city (and the poems it inspired). I would have liked to have read more of Lorca’s own words about Grenada and its environs, but the authors hold back, stating, “it would be easy to quote Lorca at every corner, but a choice has to be made.”

As for the Alhambra, the authors, careful not to indulge in trite stereotypes, go too far in the other direction and disparage the romantic descriptions of nineteenth-century visitors Irving and Gautier. Yet these passages are some of the most evocative in the entire book. Gautier calls the palace “a terrestrial paradise” and writes that the “limpidness of the water and the whiteness of the stone have no equals.” The setting sun, for the Frenchman, caused everything to assume “the appearance of jewels.” The Edwardses somewhat snidely remark that Gautier, “enraptured, was blind to the worst excesses of the city’s climate” and call him “reminiscent of a 1960s hippy wanderer” with his “exuberant facial hair and flowing locks.” Irving, for his part, “not the only foreign writer to fall under the palace’s charms,” was merely “waxing lyrical” in his imaginative writings on the palace.

The authors are at pains to be thorough, when at times a more selective approach might have been advisable. Towns that seem to offer little to tourists, and have scant connection to a literary history, are duly described. Authors who did not actually write about a place but who lived there are prominently featured. For instance, we get several pages on the life of nineteenth-century Sevillean Romantic poet Bécquer, including an excerpt from his writing about his love of language and a snippet of a poem about lovers, but the section disappointingly concludes with just one short direct quote describing a willow tree along Seville’s riverbank, long since transformed into an active port.

The design and content—not to mention weight—would not recommend the volume to be used as an on-site guidebook, so it is jarring to come across practical information buried deep in the prose. For instance, in the chapter on the little-visited industrial Huelva province: “a flat sandy plaza provi[des] ample parking” or, at the end of the following paragraph, “Needless to say, the intense summer temperatures dry both water and grasslands to parched extremes; spring is the most appropriate time to visit.”

The Edwardses have sifted through an enormous amount of material and organized it in a clear and logical, if not always rousing, manner. But the end result, perhaps due to the available sources, does not communicate a distinct spirit of place: how does the natural landscape, the built environment, the people, the climate, the light, the smells, the sounds create something specifically Andalucian? Why should I want to go there? Maybe, sitting in my house in Berkeley nearly 6,000 miles from Spain, I wanted more swirling flamenco skirts, balletic toreadors and glowering vengeful lovers.

Nina Lewallen Hufford is a freelance writer and editor with a background in architectural history. She lives in Berkeley with her family but travels whenever she gets the chance.

[

top image: “Arcos en Patio de los Leones, la Alhambra” by Javier Carro]

The authors of Andalucia dutifully enumerate the literary figures associated with each province. In the first chapter, devoted to Seville, they discuss a range of authors, from Lord Byron, Miguel de Cervantes, Théophile Gautier, and Washington Irving to the lesser-known Henry Swinburne (a Brit who traveled to Seville in the 1770s), the “idiosyncratic Englishman” and missionary (of a sort) George Borrow, Spanish writer Luis Cernuda of the Generation of ’27, and contemporary crime writer Robert Wilson. (An appendix with author profiles as well as a useful chronology linking literary/cultural events to political events are included at the end of the volume.)

While we learn a bit about each writer, and his connection to Seville (they are all men, in this chapter), we are rarely offered the opportunity to view the city through their eyes. Direct quotes are few and far between. When the Edwardses have been able to include pertinent descriptions, they are often less than enlightening. What does Swinburne have to say about the famous Seville bell tower, which he visited in 1775? “At one angle stands the Giralda, or belfry, a tower 350 feet high, and 50 square [. . . ] the Christians have added two stories and a prodigious weathercock.”

I was especially looking forward to the chapter on Granada, home to perhaps my favorite building in the world, the Moorish Alhambra palace and its gardens. The Edwardses have more to work with in this chapter: Federico García Lorca looms large over the section of the chapter devoted to the city itself. Excerpts from Lorca’s Sketches of Spain (1918) amply provide the poetic sense of place promised by the series: “Shadows slip over the bonfire that is the Alhambra . . . The Vega [plain] lies flat and silent.” We are led through Lorca’s city: the site of his family’s residences, the location of a café where he hung out with his literary circle, his college residence hall, his family’s summer house outside the city (and the poems it inspired). I would have liked to have read more of Lorca’s own words about Grenada and its environs, but the authors hold back, stating, “it would be easy to quote Lorca at every corner, but a choice has to be made.”

As for the Alhambra, the authors, careful not to indulge in trite stereotypes, go too far in the other direction and disparage the romantic descriptions of nineteenth-century visitors Irving and Gautier. Yet these passages are some of the most evocative in the entire book. Gautier calls the palace “a terrestrial paradise” and writes that the “limpidness of the water and the whiteness of the stone have no equals.” The setting sun, for the Frenchman, caused everything to assume “the appearance of jewels.” The Edwardses somewhat snidely remark that Gautier, “enraptured, was blind to the worst excesses of the city’s climate” and call him “reminiscent of a 1960s hippy wanderer” with his “exuberant facial hair and flowing locks.” Irving, for his part, “not the only foreign writer to fall under the palace’s charms,” was merely “waxing lyrical” in his imaginative writings on the palace.

The authors are at pains to be thorough, when at times a more selective approach might have been advisable. Towns that seem to offer little to tourists, and have scant connection to a literary history, are duly described. Authors who did not actually write about a place but who lived there are prominently featured. For instance, we get several pages on the life of nineteenth-century Sevillean Romantic poet Bécquer, including an excerpt from his writing about his love of language and a snippet of a poem about lovers, but the section disappointingly concludes with just one short direct quote describing a willow tree along Seville’s riverbank, long since transformed into an active port.

The design and content—not to mention weight—would not recommend the volume to be used as an on-site guidebook, so it is jarring to come across practical information buried deep in the prose. For instance, in the chapter on the little-visited industrial Huelva province: “a flat sandy plaza provi[des] ample parking” or, at the end of the following paragraph, “Needless to say, the intense summer temperatures dry both water and grasslands to parched extremes; spring is the most appropriate time to visit.”

The Edwardses have sifted through an enormous amount of material and organized it in a clear and logical, if not always rousing, manner. But the end result, perhaps due to the available sources, does not communicate a distinct spirit of place: how does the natural landscape, the built environment, the people, the climate, the light, the smells, the sounds create something specifically Andalucian? Why should I want to go there? Maybe, sitting in my house in Berkeley nearly 6,000 miles from Spain, I wanted more swirling flamenco skirts, balletic toreadors and glowering vengeful lovers.

Nina Lewallen Hufford is a freelance writer and editor with a background in architectural history. She lives in Berkeley with her family but travels whenever she gets the chance.

[top image: “Arcos en Patio de los Leones, la Alhambra” by Javier Carro]

The authors of Andalucia dutifully enumerate the literary figures associated with each province. In the first chapter, devoted to Seville, they discuss a range of authors, from Lord Byron, Miguel de Cervantes, Théophile Gautier, and Washington Irving to the lesser-known Henry Swinburne (a Brit who traveled to Seville in the 1770s), the “idiosyncratic Englishman” and missionary (of a sort) George Borrow, Spanish writer Luis Cernuda of the Generation of ’27, and contemporary crime writer Robert Wilson. (An appendix with author profiles as well as a useful chronology linking literary/cultural events to political events are included at the end of the volume.)

While we learn a bit about each writer, and his connection to Seville (they are all men, in this chapter), we are rarely offered the opportunity to view the city through their eyes. Direct quotes are few and far between. When the Edwardses have been able to include pertinent descriptions, they are often less than enlightening. What does Swinburne have to say about the famous Seville bell tower, which he visited in 1775? “At one angle stands the Giralda, or belfry, a tower 350 feet high, and 50 square [. . . ] the Christians have added two stories and a prodigious weathercock.”

I was especially looking forward to the chapter on Granada, home to perhaps my favorite building in the world, the Moorish Alhambra palace and its gardens. The Edwardses have more to work with in this chapter: Federico García Lorca looms large over the section of the chapter devoted to the city itself. Excerpts from Lorca’s Sketches of Spain (1918) amply provide the poetic sense of place promised by the series: “Shadows slip over the bonfire that is the Alhambra . . . The Vega [plain] lies flat and silent.” We are led through Lorca’s city: the site of his family’s residences, the location of a café where he hung out with his literary circle, his college residence hall, his family’s summer house outside the city (and the poems it inspired). I would have liked to have read more of Lorca’s own words about Grenada and its environs, but the authors hold back, stating, “it would be easy to quote Lorca at every corner, but a choice has to be made.”

As for the Alhambra, the authors, careful not to indulge in trite stereotypes, go too far in the other direction and disparage the romantic descriptions of nineteenth-century visitors Irving and Gautier. Yet these passages are some of the most evocative in the entire book. Gautier calls the palace “a terrestrial paradise” and writes that the “limpidness of the water and the whiteness of the stone have no equals.” The setting sun, for the Frenchman, caused everything to assume “the appearance of jewels.” The Edwardses somewhat snidely remark that Gautier, “enraptured, was blind to the worst excesses of the city’s climate” and call him “reminiscent of a 1960s hippy wanderer” with his “exuberant facial hair and flowing locks.” Irving, for his part, “not the only foreign writer to fall under the palace’s charms,” was merely “waxing lyrical” in his imaginative writings on the palace.

The authors are at pains to be thorough, when at times a more selective approach might have been advisable. Towns that seem to offer little to tourists, and have scant connection to a literary history, are duly described. Authors who did not actually write about a place but who lived there are prominently featured. For instance, we get several pages on the life of nineteenth-century Sevillean Romantic poet Bécquer, including an excerpt from his writing about his love of language and a snippet of a poem about lovers, but the section disappointingly concludes with just one short direct quote describing a willow tree along Seville’s riverbank, long since transformed into an active port.

The design and content—not to mention weight—would not recommend the volume to be used as an on-site guidebook, so it is jarring to come across practical information buried deep in the prose. For instance, in the chapter on the little-visited industrial Huelva province: “a flat sandy plaza provi[des] ample parking” or, at the end of the following paragraph, “Needless to say, the intense summer temperatures dry both water and grasslands to parched extremes; spring is the most appropriate time to visit.”

The Edwardses have sifted through an enormous amount of material and organized it in a clear and logical, if not always rousing, manner. But the end result, perhaps due to the available sources, does not communicate a distinct spirit of place: how does the natural landscape, the built environment, the people, the climate, the light, the smells, the sounds create something specifically Andalucian? Why should I want to go there? Maybe, sitting in my house in Berkeley nearly 6,000 miles from Spain, I wanted more swirling flamenco skirts, balletic toreadors and glowering vengeful lovers.

Nina Lewallen Hufford is a freelance writer and editor with a background in architectural history. She lives in Berkeley with her family but travels whenever she gets the chance.

[top image: “Arcos en Patio de los Leones, la Alhambra” by Javier Carro]